By Baker Howry, Shannon Wright, and Jamila Brinson

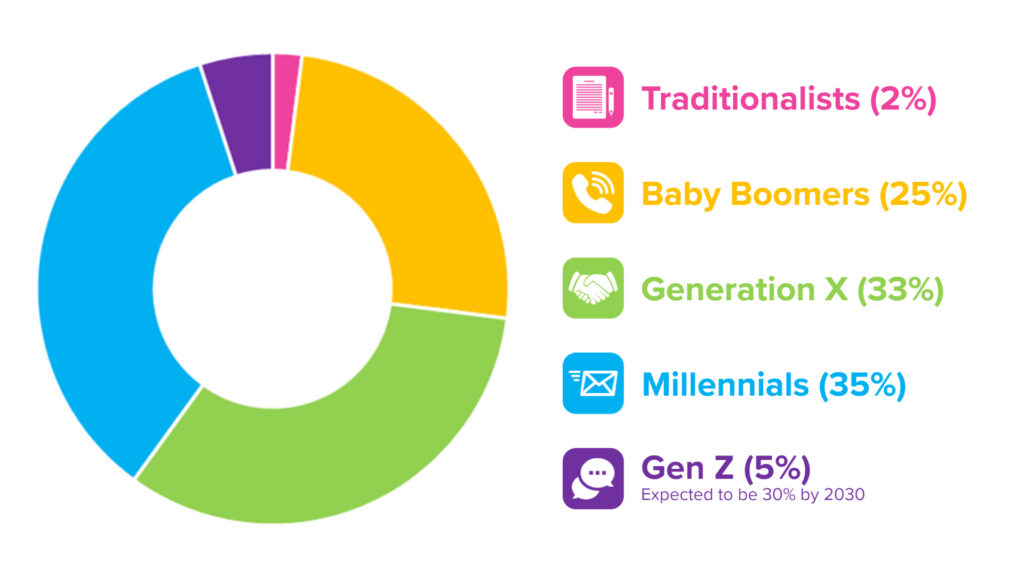

To meme or not to meme, that is the question. With millennials comprising 35% of the workforce and Gen Z expected to reach 30% by 2030, the use of emojis, emoticons, and memes in the workplace is inevitable. This article provides an overview of what emojis mean for employers, including the potential for miscommunication, how courts have analyzed them, and key considerations for risk management.

Generations in the Workforce

According to Purdue University, five generations are actively in the workforce; each generation has been shaped by major historical events and each has a preferred communication style based on technology available in the early stages of their careers.

Sources: Purdue Global and Don Sjoerdsma (LiveCareer)

Traditionalists (2%)

- Born between 1925 and 1945

- Major Events: Great Depression, World War II

- Preferred Communication Style: Personal touch, handwritten notes

Baby Boomers (25%)

- Born between 1946 and 1964

- Major Events: Vietnam War, Civil Rights Movement, Watergate

- Preferred Communication Style: Whatever is most efficient, including phone calls and face-to-face

Generation X (33%)

- Born between 1965 and 1980

- Major Events: AIDS epidemic, fall of the Berlin Wall

- Preferred Communication Style: Whatever is most efficient, including phone calls and face-to-face

Millennials (35%)

- Born between 1981 and 1996

- Major Events: Columbine, 9/11, the Internet

- Preferred Communication Style: IMs, text, e-mail

Gen Z (5%)

- Born between 1997 and 2012

- Major Events: Great Recession, school shootings, social media, COVID-19

- Preferred Communication Style: IMs, text, social media

As a disclaimer, generational differences are just one factor impacting how people communicate. Some other factors include nationality, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, neurological diversity, and education.

Potential for Miscommunication

A colleague reacts to a text message with 💀. What is this person likely conveying? If the colleague is a member of Gen Z, probably laughter!

Miscommunication between generations is a common experience for many in the workforce. Each generation has its own slang that may seem unintelligible to colleagues of a different generation. And the rise of the use of visual modes of communication, like emojis, can create even further confusion, particularly when considered internationally. For instance, the following emojis are viewed differently outside of the United States:

- “😊” in the U.S. means happiness, while in China, it can mean distrust or contempt

- “👍” in the U.S. means a job well done; in Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, it is an insulting gesture

- “👌” typically means “OK” in the U.S., while it may mean wealth or coins in Japan and anger or displeasure in Brazil

- “🥐” is a yummy, delicious, buttery croissant in the U.S., while in the U.K., it signifies that someone is opposed to Brexit

- “👼” means baby or innocence in the U.S.; in China, it may be a threat

- “💩” is literal in the U.S. but means good luck in Japan

Memes are another form of visual communication that first became popular in the mid-1990s as simple pixelated images like the dancing baby or hamsters or LOLcats. With the rise of Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms, reaction GIFs and image macros took control and now dominate meme culture. Modern day memes are more visually—rather than contextually—humorous and self-referential than earlier forms. As a result they are less intuitive and less likely to be understood by a wider audience.

The exponential growth of these visual forms of communication, coupled with up to five generations actively participating in the modern workforce, has greatly increased the potential for miscommunication. That disconnect can sometimes land employers in hot water.

Visual Communication in the Courts

At first glance, the emoticon/emoji may seem innocent or harmless, such as a simple smile, wink, or sad face used to communicate happiness, humor, or sadness. However, taken in the context or community in which the communication is used, the meaning may be interpreted differently in the eyes of the sender and/or recipient.

The first known U.S. case referencing an emoji was in 2014. Since then, cases referencing emojis have skyrocketed to 154 in 2021. As of 2021, employment discrimination is the second most common type of case in which emojis play a role. Emojis are most commonly sent through text message (61 cases), social media (35 cases), and email (17 cases).

Interpretation by the court system regarding the use of emojis and emoticons has included looking to the surrounding circumstances, analyzing the accompanying text, and asking whether the emoji materially alters the message’s intended meaning.

In Kryzak v. State, the defendant was charged with manslaughter. The defendant and the victim had been engaging in a secret romantic relationship, but the defendant would not leave her husband for the victim. On the night of the victim’s murder, the defendant texted: “Well I’m on my way (frowning face emoji).” The victim responded: “I don’t care” “You stupid b*ch.” In its decision, the court upheld the conviction for manslaughter because the evidence, including a series of text messages, shed light on the increasingly turbulent nature of their relationship. Kryzak v. State, No. 05-18-00660-CR, 2019 Tex. App. LEXIS 7786 (Tex. App.⸻Dallas Aug. 27, 2019)

Ghanam v. Does was a defamation suit based on messages posted on an anonymous internet message board in which the defendant used the “sticking out tongue” emoticon regarding the city’s purchase of two new garbage trucks. The plaintiff filed a petition for an ex parte order to depose a former city employee to determine the identities of the posters. After the circuit court granted the petition, the appeals court reversed and ordered judgment for the defendants. In its decision, the appeals court wrote: “This statement on its face cannot be taken seriously as asserting a fact. The use of the ‘:P’ emoticon makes it patently clear that the commenter was making a joke. As noted earlier, a ‘:P’ emoticon is used to represent a face with its tongue sticking out to denote a joke or sarcasm. Thus, a reasonable reader could not view the statement as defamatory.” Ghanam v. Does, 845 N.W.2d 128 (Mich. Ct. App. 2014)

In the case of Lightstone RE LLC v. Zinntex LLC, the buyer had agreed to order $2.1 million of personal protective equipment and the seller failed to deliver. The parties began negotiating a refund. After the plaintiff had sent a text summarizing the expected refund payments, the defendant responded with a thumbs up emoji. The plaintiff argued the thumbs up emoji constituted a signature of an executory accord. Rejecting the fraud claim, the court stated there were “questions of fact whether defendant intended to be bound by that emoji when only nine minutes beforehand the defendant categorically asserted he would not sign any document.” Lightstone RE LLC v. Zinntex LLC, No. 516443/21, 2022 NY. Misc. LEXIS 5925 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 25, 2022)

Takeaways

Emojis, emoticons, and memes are not a universal language, and it is ill-advised to assume any one specific definition of a visual form of communication. Even the hardware or electronic platform used to send the message can render visual forms of communication differently between the sender and the recipient. For example, Apple replaced the pistol/gun emoji with a water pistol/toy gun emoji. However, when received by a different platform, that water pistol/toy gun emoji might still appear as a regular pistol emoji based on that platform’s design, thereby possibly manifesting a completely different intent than the Apple user intended.

Attorneys can help to ensure competent diligent representation by becoming familiar with different forms of communication and their potential meaning(s) for both sender and recipient. For example, an expert in a sex trafficking case detailed how a series of sent emojis, including a crown, high heels, and bags of money, provided evidence of prostitution, noting a crown often references a pimp. If the court had omitted the crown emoji, thinking it had a universal meaning, it would have had a severe impact on the evidence. Therefore, attorneys may need the wisdom or knowledge of those unique meanings along with expertise in a particular industry to ensure the court is aware of context. The age of the parties, cultural differences, and socioeconomic status are also paramount to understanding meaning.

Likewise, employers do not want liability to rest on a court’s interpretation of an employee’s emoji or meme. So, it is important for employers and management to consider ways to increase effective communication between employees of all generations, as well as strategies to reduce the employer’s exposure to potential litigation stemming from miscommunication.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For questions regarding the content above, please contact Baker Howry, Shannon Wright, Jamila Brinson, or a member of the Labor & Employment practice.

Meet the Team

Baker Howry is an attorney in the Houston Trial & Appellate Litigation practice. She assists clients on complex commercial litigation issues as well as white collar defense involving healthcare fraud and abuse. In 2020 and 2021, she served as a summer associate at the firm, preparing memoranda involving CERCLA lessee liability and real estate foreclosure and working on internal contract documents regarding nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Prior to Jackson Walker, Baker worked in the Government Affairs office of the American Dental Association as the Lead Project Assistant for the Regulatory and Congressional Affairs team and as the ADPAC Senior Project Assistant.

Baker Howry is an attorney in the Houston Trial & Appellate Litigation practice. She assists clients on complex commercial litigation issues as well as white collar defense involving healthcare fraud and abuse. In 2020 and 2021, she served as a summer associate at the firm, preparing memoranda involving CERCLA lessee liability and real estate foreclosure and working on internal contract documents regarding nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Prior to Jackson Walker, Baker worked in the Government Affairs office of the American Dental Association as the Lead Project Assistant for the Regulatory and Congressional Affairs team and as the ADPAC Senior Project Assistant.

Shannon M. Wright is an attorney in the Houston Trial & Appellate Litigation practice. She assists businesses in resolving commercial disputes including breach of contract, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and negligence. During her time as a summer associate at the firm, Shannon handled research and analysis for various stages of commercial litigation in cases involving liability for injuries to independent contractors, UDJA, adverse possession, discrimination/retaliation, and service mark infringement. She also served as a judicial intern for federal judges Alfred H. Bennett (Southern District of Texas) and Gregg J. Costa (Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals) in 2020.

Shannon M. Wright is an attorney in the Houston Trial & Appellate Litigation practice. She assists businesses in resolving commercial disputes including breach of contract, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and negligence. During her time as a summer associate at the firm, Shannon handled research and analysis for various stages of commercial litigation in cases involving liability for injuries to independent contractors, UDJA, adverse possession, discrimination/retaliation, and service mark infringement. She also served as a judicial intern for federal judges Alfred H. Bennett (Southern District of Texas) and Gregg J. Costa (Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals) in 2020.

Jamila M. Brinson is board certified in Labor and Employment Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. She advises employers and management on the gamut of employment laws and regulations that impact their workplaces, including in the context of a merger or acquisition, and effectively defends employers and management in employment litigation. Jamila completed a Certificate in Leading Diversity, Equity & Inclusion through Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences, and chairs Jackson Walker’s Diversity & Inclusion Counseling practice counseling clients on diversity, equity and inclusion related issues, including the effective formation and implementation of employee resource groups.

Jamila M. Brinson is board certified in Labor and Employment Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. She advises employers and management on the gamut of employment laws and regulations that impact their workplaces, including in the context of a merger or acquisition, and effectively defends employers and management in employment litigation. Jamila completed a Certificate in Leading Diversity, Equity & Inclusion through Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences, and chairs Jackson Walker’s Diversity & Inclusion Counseling practice counseling clients on diversity, equity and inclusion related issues, including the effective formation and implementation of employee resource groups.